Ankitha is a joyous, seven-year-old who lives in Alabama with her parents. She has been attending a School for the Blind the past five months and is nearing the completion of kindergarten. This is the longest Ankitha has been in school, uninterrupted. When she first entered a small, public Pre-K 3 class, we never would have imagined how quickly her life would be turned upside down with a Stage IV cancer diagnosis shortly thereafter.

We tried again a year later and enrolled her at our local, public Pre-K 4, only to have it disrupted by a worldwide pandemic, “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2″ (SARS-CoV-2). Nine months later she was diagnosed with a very rare primary immune deficiency, and we were advised to continue to keep her home and quarantined until further notice. She was five at the time. I am not a teacher by trade, nor have I ever been inclined to become one. I was also, at the time, only a year and a half “acquainted” with my daughter’s visual diagnosis of stage-4, Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP). You see, my daughter was born in India and weighed 1.2kg at birth and left with a very loving orphanage on day one. Her ROP was discovered twenty-eight months later when I brought her home to the United States and at that point treatment was no longer a viable option. When I was advised to keep her home until her medical team learned more about her new primary immune deficiency disease, I knew I needed to learn how to teach my daughter in the interim. That is when I enrolled in The University of Northern Colorado’s, Special Education with a Visual Impairment Emphasis, Master’s Program.

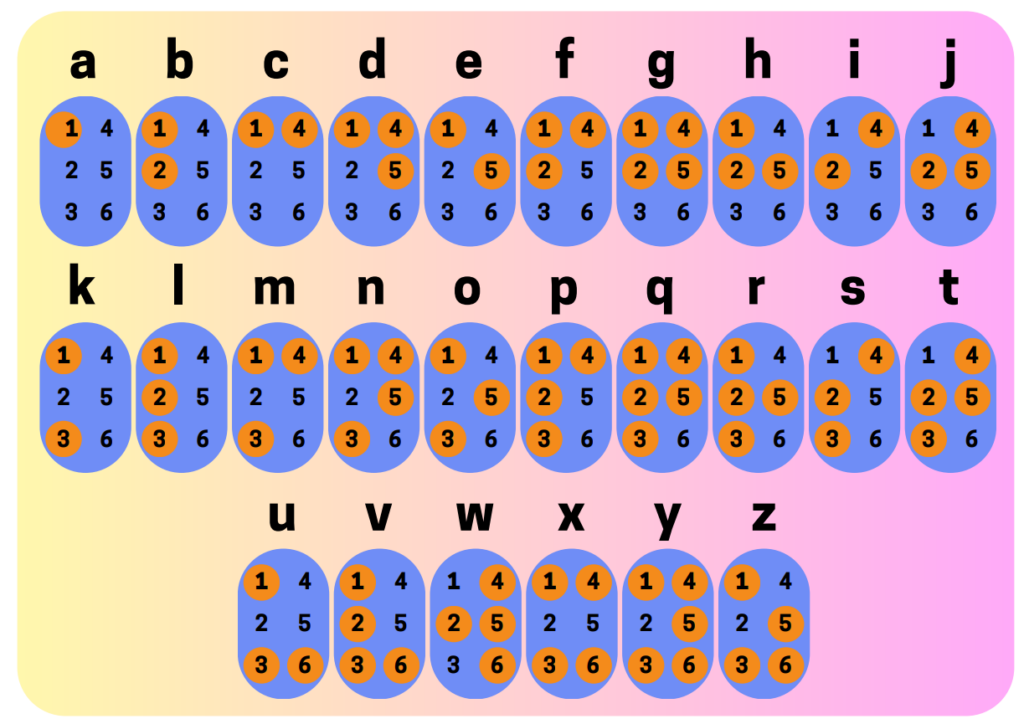

I learned within seven months of the program that she needed more than I could offer her at the time in terms of her functional vision, learning media, assistive technology, orientation and mobility, speech, and occupational needs. I knew I had to do whatever was in my power to get her the support she needed. Fortunately, her medical team and I agreed upon a contingency plan, and I was able to enroll her at the Alabama Institute for the Deaf and Blind (AIDB). Given that she had no prior exposure to braille, other than my master’s level braille books, I would say that she rapidly acquired the basic skills necessary to braille. She is currently learning how to braille contracted letters, and I am confident that she will be brailling words soon. I learned that the activities and play she engaged in while at home during quarantine, such as playdoh, slime, pouring buckets of rice or water, and kneading dough helped her develop the hand and finger strength/dexterity needed to use the braillewriter.

There was a time, not too long ago, that I was greatly concerned for my daughter’s educational future. Afterall, the unknown is a frightening place to reside. I knew she would need to learn braille and other assistive technology skills to be able to successfully access the curriculum. I am sharing my experience, our journey, in hopes of letting anyone out there reading this, experiencing similar emotions, know they are not alone. I began working at the school where my daughter attends and I am truly inspired almost daily by the students’ abilities and determination.