UEB Math Online

UEB Math Online is an e-learning braille course for professionals and parents who wish to learn Unified English Braille mathematics.

Mathematics will be more accessible to students across the globe who are blind through the innovation the Australian organization Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children (RIDBC). In response to the growing need for STEM skills in Australia and overseas, RIDBC has today launched UEB Mathematics, an online course that enables teachers and parents to better support braille-using students.

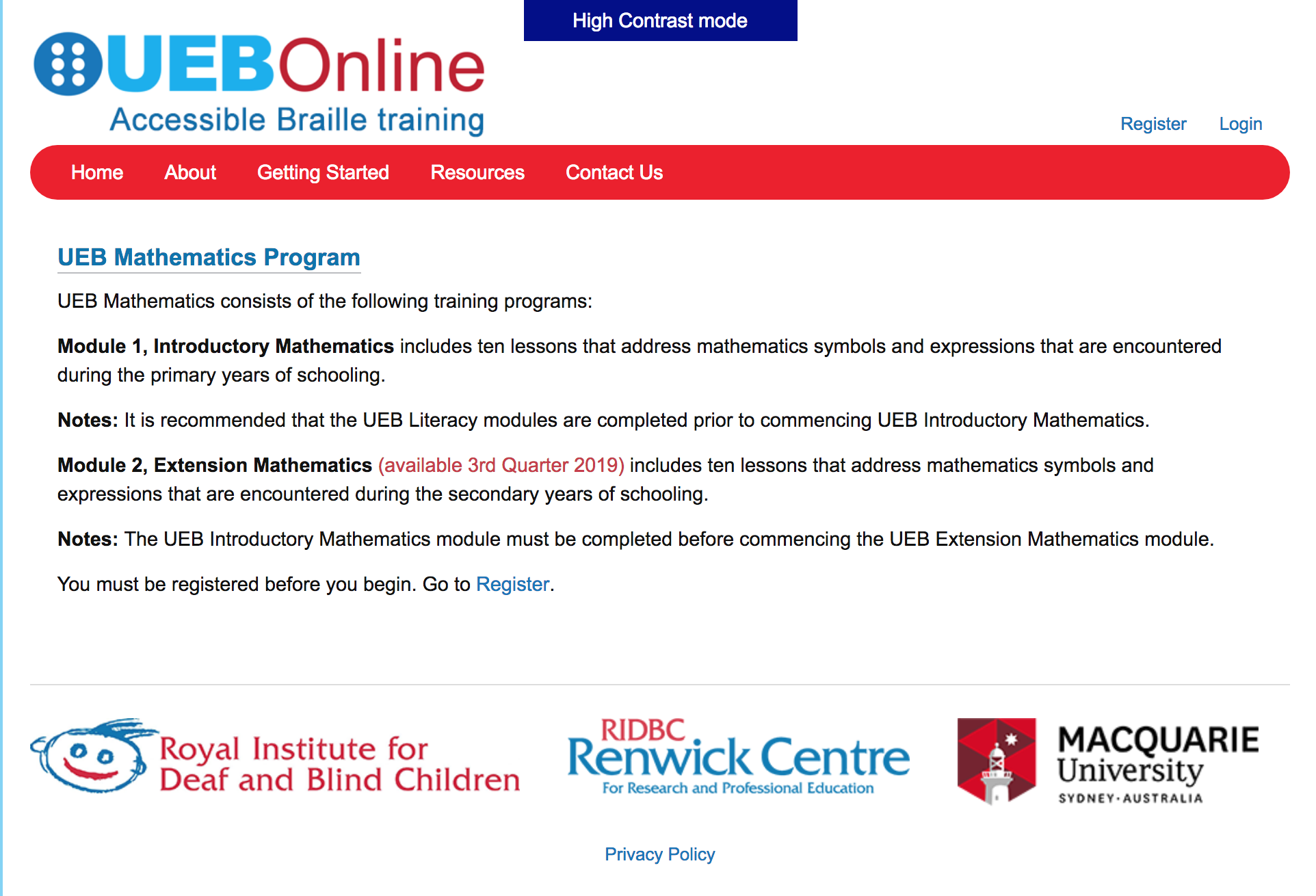

UEB Mathematics, an addition to the UEB (Unified English Braille) Online e-learning platform, enables professionals and parents to understand and connect language, literacy and mathematics development in children with vision impairment, and to plan learning experiences that are inclusive of those children who use the medium of braille.

What is UEB Online?

An Australian innovation, UEB Online, the first e-learning braille course for professionals and parents, was launched in 2014 with a goal to increase braille literacy in Australia and globally. Since its inception, more than 18,000 people in 184 countries have taken part in the course.

Now, the team behind UEB Online hope that increasing access to braille for mathematics will open up more STEM career opportunities for people with vision impairment in Australia and across the globe.

Dr Frances Gentle, Lecturer at RIDBC Renwick who led the project to create UEB Online, says the new UEB mathematics training courses are designed to promote equitable access to STEM subjects for braille users. “Equitable educational opportunity for children who are blind requires teachers who understand the braille code and how to modify print-based activities in the classroom.”

“We want to enable students with blindness to continue studying mathematics into their senior school years and as a result, increase access to careers in STEM-related fields. Achieving this aspirational goal requires teachers and parents who understand Unified English Braille in literary and mathematical contexts.”

In her role as President of the International Council for English Braille, Dr Gentle says she has witnessed the positive educational impact when braille-using students have the support of people who understand their code. “It really helps when classroom teachers can read braille text but equally, when parents can use it,” she said.

“Knowledge of braille enables parents to share the joys of reading and writing with their child, whether it is assistance with homework, notes of encouragement or birthday cards in braille.”

Dr Gentle also says that the ability to read braille amongst the sighted community is essential. “It’s critical that we increase the number of people who can use and read braille so that we can continue to teach it and ensure that children with blindness have equitable access to education and employment.”

Chris Rehn, Chief Executive at RIDBC, says that keeping Australia at the global forefront of service and technological innovation is an important goal for the organisation. “We are committed to providing the highest quality services and level of care for Australians with vision and hearing impairment, and innovations such as UEB Mathematics play a critical role in this. With mathematics identified as a vital skill for the future, ensuring students with vision impairment have equal access to education is crucial.”

The online training programs in braille literacy and mathematics can be accessed at https://uebonline.org/ and offer both free courses and paid certification options.

What is RIDBC?

RIDBC is Australia’s largest non-government provider of therapy, education, cochlear implant and diagnostic services for people with hearing or vision loss, supporting thousands of adults, children and their families, each year. Services are provided from 18 sites across Australia and through an outreach service that supports clients living in regional areas.

RIDBC is a charity and relies heavily on fundraising and community support to be able to continue to make a difference in the lives of children and adults with vision or hearing loss.

For media enquiries, please contact: