What does “Literacy” mean for children with multiple disabilities?

All children, regardless of whether or not they have a vision loss or additional challenges, learn through repeated and frequent exposure to meaningful hands-on experiences in order to develop basic concepts that are the foundation of literacy. In this sense, literacy is much more than learning to read, whether it be in braille or print, as it begins with an understanding of one’s environment, including people, activities, and routines. Learning to communicate about these experiences may be through speech, sign language, objects, or some combination of these. Literacy is a broad topic that encompasses many different forms, including print, braille, objects, speech, sign language, and other symbol systems.

With this broader focus on language (including sign language), literacy includes recognizing objects, pictures, or other symbols, and using them to communicate. Making choices, anticipating events, following simple recipes, creating or “reading” lists, and other forms of self-expression are all part of functional literacy.

What do we mean by “multiple disabilities”?

Children with multiple disabilities are not a homogenous group. This term encompasses a wide range of functioning levels, depending on the severity and specifics of each type of disability. A student who is totally blind and profoundly deaf will have different educational needs from a child who has low vision and mild cerebral palsy. Some students may be academically close to grade level, and in need of emotional support, or have physical challenges that make it difficult for them to hold materials or write with a braillewriter or pencil. Students with significant intellectual impairments may need to have extensive modifications to the curriculum, educational materials, and instructional techniques. It is up to each educational team to assess the student and determine his or her individual needs. We offer ideas and suggestions from the field in the assumption that teachers, families, and others working with a child will evaluate comprehensively and make individual determinations of what is appropriate.

Please see the section on Struggling Readers for information about students with visual impairments and specific learning disabilities.

Do students who are deafblind have the same needs as other children who have multiple disabilities?

As above, children who are deafblind are a diverse group, depending on the amount of vision and hearing they have, at what age they lost their vision and hearing, the etiology of their sensory impairment and whether they have other disabilities. There is a specific section devoted to strategies that are unique to students with both visual and auditory loss. Many of the practices focusing on communication, routines, and concept development are similar to those used for children with multiple disabilities. Children who are deafblind who are at the same academic grade level as their peers are sometimes called “proficient communicators”. Please see also the Texas Deafblind Project website for more information about this group.

How can we engage children in developing foundational concepts?

Because children with multiple disabilities often have limited experiences and access to the world, they may not fully understand everything that is happening around them. Basing lessons on meaningful and interesting experiences can help motivate students to actively participate in literacy activities. Experiences from the child’s own life that are familiar and concrete are often a good place to start. For example, daily routines such as bathing and dressing, helping to prepare meals, going to a restaurant, or visiting friends and relatives are common experiences that most of us have. Talking about these events before they happen and developing a process for referring back to them afterwards is an important foundation for reading stories about other life experiences.

Including the child in hands-on activities using real objects can help to develop an understanding of what objects are used for, as well as basic concepts about the world, such as cause and effect and object permanence. Daily activities can also give children experience with attributes, such as big/little, wet/dry, heavy/light, and other concepts that are essential to the understanding of same/different and comparative thought.

How can we make literacy experiences meaningful to children with multiple disabilities?

It may be daunting at first to imagine how to include children with significant multiple disabilities in early literacy experiences. If they cannot see the book, and if additional challenges make it difficult for them to hear, to understand, or to help to turn the pages, parents and teachers may be at a loss on how to make this experience meaningful.

Meaningful hands-on experiences benefit all children when they provide an opportunity for active engagement, language enrichment, and concept development. Every time children get to DO something fun, they are building potential stories. These experiences can be the foundation of literacy through the creation of memory boxes, retelling the sequence of events that happened, and writing experience stories.

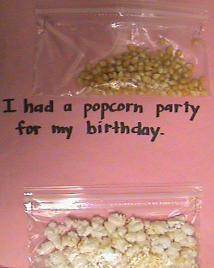

For example, if a child loves to make and eat popcorn, this activity can be made into a literacy activity by collecting parts of the activity (e.g. unpopped kernels of popcorn, pieces of popped popcorn) and writing a few sentences about the activity with the child.

Sequence from Real Objects to Tactile Symbols

When presenting materials to students with visual impairment and multiple disabilities, begin with real objects that are familiar to the child. These can be arranged on a sequence board or boxes to relay information about an experience. This is the equivalent to pictures that are used for sighted children beginning literacy. For example, begin with a spoon, bowl, and packet of pudding and talk to the child about the experience of eating the pudding. “Do you remember when we had pudding at snack time today? First we got the spoon from the drawer, then we got the bowl out of the cupboard, and then we got the pudding out of the refrigerator. It was chocolate. Yum! I love chocolate!”

After a student recognizes these objects and demonstrates understanding of the function of the spoon, bowl, and pudding packet, these objects can be paired with tactilely significant portions (e.g., the handle of the spoon that she will grasp, a ring like that hanging on the metal bowl, an empty packet) and these two can be compared and used together in the sequencing. Eventually, when the student is able to transfer their understanding to this partial object, it can be paired with a less concrete representation – a tactile symbol. The journey from reliance upon the real objects to meaningfully using an abstract tactile symbol can take time, and consistent modeling. Some students may progress to braille, while others will find tactile symbols the most meaningful systems to support communication and build reading and writing skills.

We encourage you to explore related sections, including: