Exposure to pictures is a prerequisite to successful literacy.

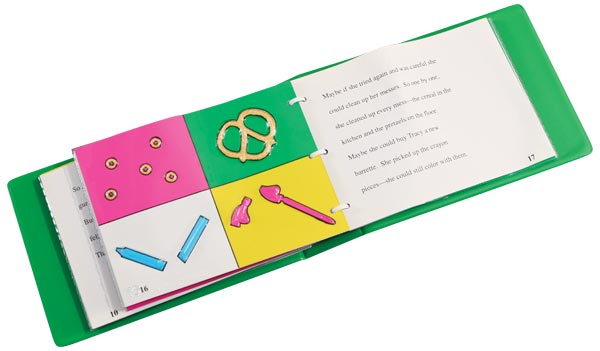

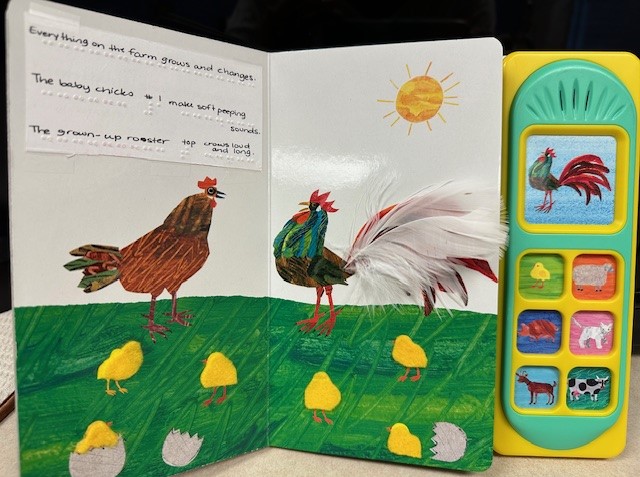

Pictures provide the first step to literacy for sighted children and serve as a bridge between the pages of the books they will eventually read and the three-dimensional world around them. Just as sighted children are first captivated by pictures and then drawn to reading print, many children who are blind respond in the same way to tactile representations. The fascination with the feeling of tactile graphics can lead to further development of the child’s interest in reading braille, especially when the tactile graphic is immediately recognized as a familiar object. I can’t begin to count the number of times, in my 14 years of teaching, the excitement of my littlest students when they recognized the pretzels and cereal in the Tactile Treasures kit or in “Jennifer’s Messes” from the On The Way to Literacy series, but had no interest yet in identifying the letters A or B on the page. Thus, age appropriate tactile graphics should not be considered “an advanced braille skill,” but just the opposite in that exposure to pictures is a prerequisite to successful literacy for all children.

Begin by developing concepts through real experiences.

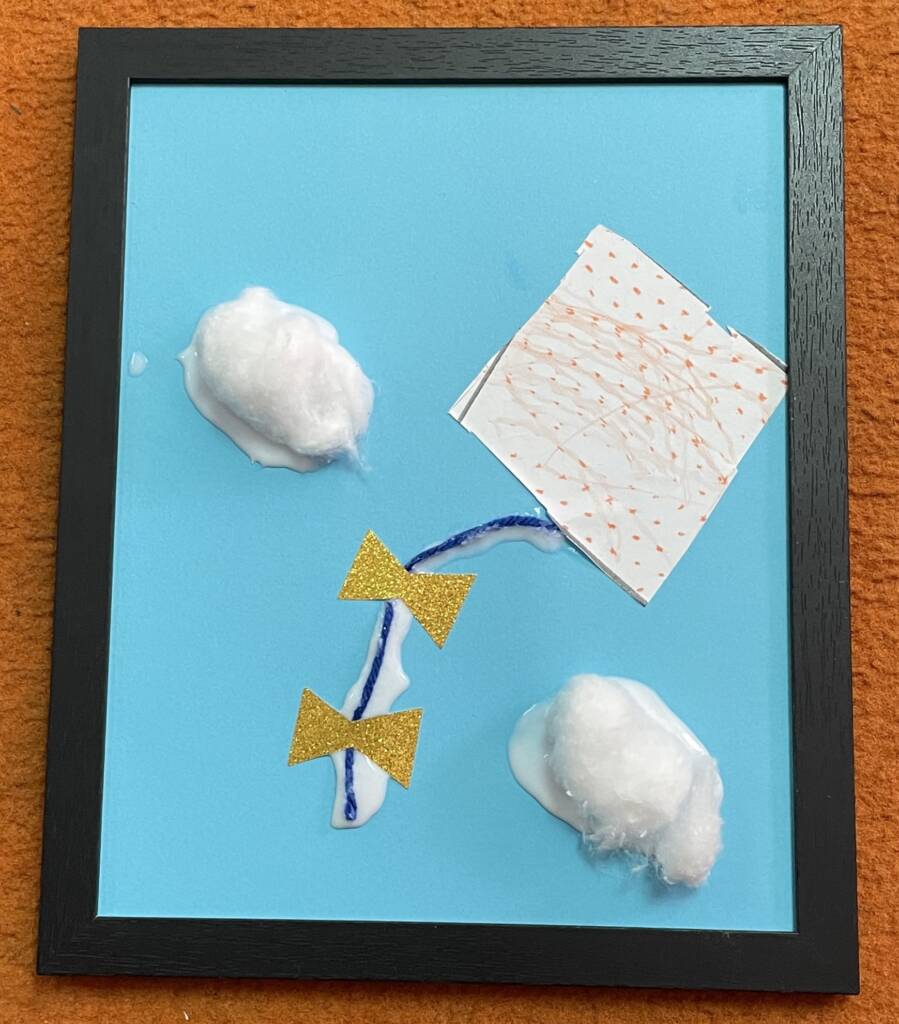

Introducing students who will become braille readers to tactile pictures can enhance their conceptual development as well as their educational performance. However, they must be able to connect the abstract tactile representation back to something concrete in order for the image on paper to even begin to make sense. A sighted learner has seen a tree outside and can relate the picture in their book right back to that tree, but a child without vision needs to have experiences with the tree before trying to color one using a raised coloring page. If you cannot see, and only walked up and touched the bark of a tree, how would you know that there are also branches and leaves? Probably through stories and discussions about Autumn, or you climbed a tree right alongside your sighted cousins growing up as I did.

Establish the link between the word, object, experience, and tactile pictures.

Now imagine if you were shown a tactile graphic of something as simple as a single leaf. You have not grown up looking at trees, nor have you had the experience of playing in a pile of leaves. The tactile graphic would, of course, make no sense and have no relevance to you. This is why it is imperative that children who are blind have real concrete experiences so that they can first attain accurate perceptions of objects and then begin to transfer these experiences to a rather symbolic representation. Furthermore, during this first concrete to abstract experience, the type of leaf shown in the tactile graphic should be the same type of leaf that was touched, as leaves can be very different in shape. It is also important that the tactile graphic be labeled as “oak leaf,” “maple leaf,” etc. Labels are an essential element of learning to associate tactile representations with words for braille readers. Playing a guessing game with a tactile coloring page without experience or contextual knowledge can lead to confusion and frustration. Therefore, establishing the link between the word, object, experience, and the tactile picture is the only way to guarantee both success and enjoyment for children as they explore their first tactile pictures.

Spatial concepts and exploration techniques are essential to make sense of information.

Tactile graphics, no matter how carefully designed, are meaningless in the hands of anyone who lacks the associated concrete experiences, the spatial concepts, or the exploration techniques to make sense of the information shown. A prime example which I frequently encountered with my totally blind students was when a side view of an animal was depicted. The students would want to know why the rabbit only had one ear or where its other two feet were. A great way to make such perceptions clear is to use a stuffed or plastic toy rabbit so that the student can see the three-dimensional object in the same position as demonstrated in the picture. Think about a coloring page of a car as another example and realize why the child might ask where the other two wheels are? This is when the little toy car becomes a priceless teaching tool in that the child can understand what it means to only be viewing the side of the car that is closest to him as it sits on the table. But remember that the association must also be made between the toys and real experiences such as exploring a parked car or petting the bunny at the petting zoo.

Understanding side view, top view, rotation, etc. are vital skills later on for the much more difficult expectations on high stakes tests, and the best way to do this is with concrete examples. You have undoubtedly encountered the types of math questions when four layouts of six squares are shown and students are asked which particular set of squares would fold together to make a cube based on their layout. Again, using three-dimensional objects which can be laid flat in the same order as the picture and then folded, if the correct layout is shown, will help develop this complex spatial thinking. But, before getting overwhelmed with the tougher questions such as this one, just remember the fun you can have teaching kids to use building sets, and even origami to begin conceptualizing relational scenarios very early on before they ever encounter such a task.

In summary, children who are blind need concrete objects and real world experiences, but undoubtedly benefit from repeated exposure to tactile pictures to color and explore. Preschoolers and kindergarteners without simple tactile graphics are missing an enormous percentage of what their sighted peers are learning incidentally on a daily basis through pictures alone. Tactile graphics, when paired with concrete experiences and fun, provide not only the picture, but offer equal opportunity for participation alongside sighted peers, develop spatial understanding, and most of all, deliver an essential component of literacy.

Other Ideas for Getting Little Hands Ready and Learning How Real World Objects Become Abstract

- Build and build some more with different types of toy blocks, gears, etc.

- Experiment with Play-doh™ and all those molding sets.

- Trace around a leaf, their foot, or something else of their choice.

- Make crayon rubbings of objects, such as a quarter.

- Use very simple stencil outlines to help kids be successful at drawing favorite shapes or animals.

- Don’t forget scented crayons and placing texture under the paper to add to the coloring experience. Try the Color-By-Texture Marking Mat from APH.

Enjoy bringing pictures to life!