Stephanie Duesing is a parent to Sebastian who has CVI (Cortical/Cerebral Visual Impairment). She is an educator, advocate, and author of the book, Eyeless Mind: A Memoir About Seeing and Being Seen. Stephanie talked to us about her journey and shares with us some insightful wisdom.

Tell me about yourself and your son Sebastian.

Thank you! I’m so delighted to contribute to this forum on CVI. As you mentioned, I am the author of Eyeless Mind: A Memoir About Seeing and Being Seen. I am an author, speaker, and CVI advocate. My son Sebastian is the only person in the world known to process his vision verbally, which means that he sees with words like a bat sees with sound. Dr. Lotfi Merabet, associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, associate scientist at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, and the director of the Laboratory for Visual Neuroplasticity at Schepens Eye Research Institute, published this paper on Sebastian’s use of verbal mediation to process his vision in collaboration with his team and Dr. Barry Kran, professor at the New England College of Optometry and the head of optometrics at the New England Eye Low Vision Clinic at the Perkins School for the Blind.

Eyeless Mind is the true story of how an ordinary music teacher made a major medical discovery in the field of visual neuroplasticity, and the horrific medical malpractice and abuse we experienced just to get a diagnosis for CVI.

You had quite a time there. How long did you teach music before you discovered Sebastian’s CVI?

Yes, we had a very challenging time. Unfortunately, I think our story is pretty relatable because I have met so many CVI families who are going through ridiculous, absolutely heartbreaking experiences just like we did. My son’s CVI is an entirely invisible disability, but the challenges CVI families face are often extraordinary even when the CVI symptoms are obvious.

I began my career teaching middle school music and chorus, back in the day when seventh and eight grades were routinely called “junior high.” Everyone told me I was crazy to want to teach middle school, but I still really enjoy that age group. Tweens and teens are so capable and loyal. I studied junior high music teaching methods with the wonderful Professor Mary Hoffman, PhD. at the University of Illinois at Champaign/Urbana. She was internationally renowned in the field of music education. She was a distinguished international guest conductor, clinician, and a dynamic speaker who also arranged many musical compositions for middle school chorus while authoring five public school textbooks, such as World of Music and The Music Connection (Silver Burdett Co.) I have vivid memories of Dr. Hoffman in my junior high music methods class belting out the lyrics, “What shall we do with a drunken sailor?” What I remember most about Dr. Hoffman, aside from her love of sea shanties, was her passionate belief that all adults should be life-long learners. She insisted that educators must model what they claim to do.

Never in a million years would I have guessed that I would become a life-long learner in cerebral/cortical visual impairment (CVI) and the science of visual neuroplasticity!

I chose to teach at a school district that was demographically diverse because I believe that education is a human right. The school district where I taught was the first school district in Illinois to practice full inclusion of students with disabilities. I am proud that I advocated for the change. I enjoyed teaching students with all types and levels of severity of disability.

I had several students who I know now almost certainly had CVI, but were misdiagnosed with autism. I can’t write about what was done to these children thirty years ago by the mostly well-intentioned administrators who, nevertheless, obviously viewed non speaking individuals as somewhat less than human. I am proud that I advocated fiercely on behalf of these vulnerable children, and I’m proud of my reputation as a “difficult” teacher for my efforts.

My son Sebastian does not have autism, nor does he appear to be autistic. However, like my former students and many other children who have CVI, Sebastian was repeatedly misdiagnosed. Sebastian was fifteen when we finally figured out he had CVI. His form of CVI has always been an entirely invisible disability, and getting a diagnosis and a little bit of orientation and mobility (O&M) training for my blind son was the most difficult thing I’ve ever done. I know that so many parents are facing similar struggles today, which is the main reason we felt compelled to speak out publicly.

It sounds like you have had wonderful role models and a lot of experience with children. Tell us about why Sebastian has CVI.

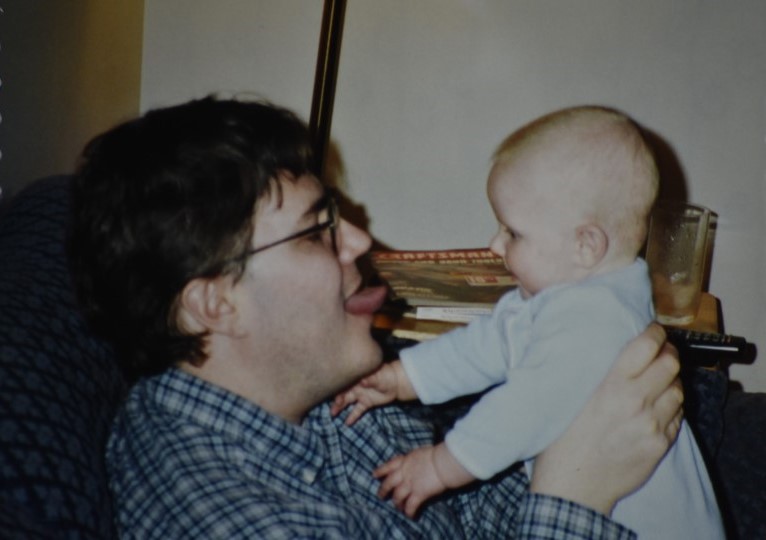

That’s true! I have been extremely fortunate to have had many brilliant teachers in my life. I enjoyed teaching middle school music and chorus for ten years, and then I got pregnant with my son Sebastian. I was diagnosed with preeclampsia three days before my due date, and then nearly died when I coded from the epidural. It was so miraculous to then wake up from six hours of unconscious labor and to give birth to what I was told was a perfectly healthy baby. Sebastian made eye contact with me when the nurse laid him on my stomach. That moment is so vivid for me.

The medical staff told us that he was fine, and that he had nine on his APGAR score. He latched on and nursed with no problems. He was the picture of a healthy newborn to my eyes. There are no words to describe the relief and joy I felt that my baby was safe after the trauma of my own near death.

I had no idea how incredibly wrong I was. I wonder every day how our lives would be different if we’d known Sebastian had CVI early on, and how much trauma and terror my son could have avoided if there had been universal, routine, medically and scientifically accurate screening for CVI.

Why didn’t you notice that there was something wrong right away?

That’s a great question, and I’m glad you asked it. Although Sebastian is my first and only child, I’ve been around a lot of babies, including those who were not neurotypical. I did quite a lot of babysitting and nannying in high school and college.

In the days and weeks immediately following Sebastian’s birth, Sebastian seemed like a perfectly healthy, neurotypical baby. I did notice early on that he seemed to sleep more than all my other friends’ babies did. I brought this concern up two or three times at Sebastian’s wellness visits in those first few weeks. I was given the condescending “you are a too-anxious first-time mom” treatment from the doctor each time, and the doctor said that he was fine. He said that I just had a very sleepy baby.

In all other respects, Sebastian seemed to be a perfectly healthy, happy baby. He was very easy and engaging. In a few weeks, even that excessive sleepiness disappeared. Although Sebastian has severe CVI, is almost completely blind, and has no ability to recognize faces, we have photos of him making regular, consistent eye contact from his earliest days. We also have photos of him using visual guidance of reach at a developmentally appropriate age.

Most children who have CVI are developmentally delayed. Why do you think Sebastian was not?

I believe that the reason that Sebastian had all normal developmental milestones is because he received intensive music and movement therapy from birth. The vast majority of children who have CVI are severely developmentally delayed; Sebastian had all normal developmental milestones even though he’s almost completely blind. The only explanation that I have for Sebastian’s wonderful physical development was all of the music and movement therapy he received – just for fun!

From my education as a music professional, I was very much aware that music and movement had tremendous neurological benefits in early childhood. Parents should know that there are decades of research demonstrating the neurological benefits of music in early childhood. At the time, I had no idea that the songs, dances, musical games, finger plays, and body awareness rhymes that I was doing with Sebastian would have any spectacular physical effect, because I didn’t know that Sebastian had CVI. I didn’t know he was at risk for developmental delays.

Tell us more about music and the brain.

Music and brain researchers have known for years that the vast majority of developmental delays are rooted in the inner ear. The inner ear has two functions: listening/hearing, and the vestibular (balance and coordination.) Early childhood music educators know that the listening/hearing and the vestibular functions of the ear are complementary. If one function is out of whack, then the other function is as well. Combining music with movement helps both systems to work together.

Now that we are beginning to understand the connections between our visual processing and auditory processing systems, and we are finally starting to recognize central auditory processing disorder (CAPD) as a common companion disorder to CVI, it behooves us to educate parents of at-risk newborns about the proven benefits of music and movement as soon as possible. Music and movement in early childhood has been proven to vastly assist young children in all areas of physical development involving balance, coordination, proprioception, and fine and gross motor skills. It also has been repeatedly shown to greatly improve auditory discrimination, language development and the academic skills of reading and math ability, as well as IQ.

I have no time machine to transport me back to Sebastian’s first year, and I have no magic cloning machine so that I could create a control version of Sebastian who would receive no music training to compare with the version of him that did. What I have is decades of published scientific research to support my beliefs.

Given the severity of the brain damage Sebastian suffered from his traumatic birth, he should have been developmentally delayed. I believe Sebastian had all normal developmental milestones because he experienced a great deal of music and movement in his earliest years, which strengthened his vestibular development. Although Sebastian has a serious auditory processing disorder which, among other symptoms, prevents him from being able to hear well at the same time as he is seeing, he has outstanding comprehension of spoken language. Early exposure to music is proven to help children hear and distinguish the different sounds that make up speech.

Children who have CVI have a great range of presentations of symptoms. Let’s go back to facial recognition. Why do you think that Sebastian was making eye contact even though he wasn’t recognizing your face?

Eye contact and the behavior of looking at faces is such an important topic. Looking at faces is an ancient behavior necessary for helpless, human infants to bond with their parents. Babies need to be adorable to survive. Looking and smiling at caregivers’ faces is instinctual. We’ve known for many years that infants who have CVI often avoid looking at faces. That’s a crucial behavior to notice as lack of eye contact is definitely a common symptom of CVI.

However, just because we know that lack of eye contact is a common warning sign of CVI, we can’t assume that the opposite is true. We can’t assume that a child exhibiting regular, consistent eye contact has typical vision. We’ve known for decades that even severe CVI can be an entirely invisible disability.

Just look at the case of the famous neuropsychologist Dr. Oliver Sacks. He also appeared to be typically sighted despite having both prosopagnosia and topographical agnosia. He suffered terribly from not being diagnosed early on and receiving orientation and mobility training. He felt he missed out on so much in life, and he did. Sebastian suffered in the same way.

Sebastian has something that Professor Gordon Dutton calls “affective blindsight.” That means that Sebastian recognizes and responds to facial expressions, even though he can’t recognize the faces themselves. Watching for facial expressions is a powerful reason for a baby to look at faces, even a baby as severely affected by CVI as Sebastian was. I think that’s why Sebastian has always looked at faces and appeared to make eye contact.

CVIers tell me that they routinely are accused of faking their blindness/vision impairment because they looked at something or someone. CVI is not magically different from ocular vision impairments; People with either condition can look at people and objects, yet still be visually impaired/blind.

People with ocular vision impairments would be rightfully horrified and offended if their eye doctor dismissed their vision issues simply because they happened to look at the eye chart when they sat down in the optometric chair. People who have CVI deserve the same compassion and respect. Never in human history has it been possible to tell what another human being is seeing just because their eyes were pointed in the right direction. Looking at a face isn’t the same as seeing a face.

I can see that you are very passionate about this topic. Why is it so important to you?

Thank you, yes. I am deeply concerned about the confusion on this topic in the low vision community. First, I know that if my child could be walking around appearing to be completely typically sighted, yet be almost completely blind, that anyone could be. Since Eyeless Mind came out, I’ve become friends with several adults and teens who have CVI, all of whom went undiagnosed for years, or even decades. Like both my son and Dr. Oliver Sacks, they all suffered terrible trauma because their need for orientation and mobility training with a white cane went unrecognized. Many of them suffered horrible educational abuse as well.

It is terrifying to be blind and to have absolutely no one around you who understands or provides the help that you need to be safe and to learn. Blind and visually impaired people who are denied O&M suffer emotional trauma akin to torture. Many people who have CVI, including Sebastian, were actively, deliberately denied educational and life-saving habilitative services because they (or the child) were unable to “perform ” stereotypical ocular blindness behaviors to the satisfaction of their typically sighted assessors.

The most frustrating thing is that, like Sebastian, all of my friends who have CVI were perfectly capable of describing what their CVI symptoms were (once they knew that they had CVI.) All of them, including Sebastian, were perfectly capable of explaining what services they needed, or what supports would be helpful to them. They just weren’t believed.

I’ve read recently that approximately one in thirty students in a regular education classroom have symptoms of CVI. It’s crucial that medical and educational professionals recognize that CVI can be an invisible disability, because I believe that there is a huge population of people suffering unnecessarily. We need to move past outdated assumptions about what people who have CVI look like – or behave like – and develop better, scientifically and medically accurate universal screening tools for toddlers. We can’t continue to refuse educational and habilitative services to CVIers for failing to perform inaccurate and stereotypical ocular blindness behaviors for people who don’t understand CVI.

In Eyeless Mind, you describe in raw detail many unfortunate encounters that you had with medical professionals on your journey to get Sebastian a diagnosis for his CVI. What are some other common misconceptions about CVI? Are you seeing changes in the low vision community since you went public?

Oh, yes! There are still so many misconceptions about CVI. Thank you for asking this question. There has been tremendous progress in the CVI community since 2017, fortunately. I am thrilled that Perkins has come out with the new CVI Protocol. Having an objective, research-based, inclusive assessment tool here in the U.S. for children who have CVI is fundamental to real change.

In addition, the Laboratory for Visual Neuroplasticity, which is directed by Dr. Lotfi Merabet, is also bringing forth new research regularly. Just the information that they are gathering using their eye gaze tracking software is opening up new possibilities for universal screening. I’m so optimistic for the future for all children who have CVI to be identified early and to begin to receive appropriate educational and habilitative services.

I’m also incredibly grateful for the many efforts by truly gifted, caring scientific and medical experts in the field to provide real, accessible learning opportunities for parents, educators, and medical professionals that are grounded in actual scientific research. Dr. Barry Kran, the director of optometrics at the NEELVC at Perkins, has been working tirelessly to educate his optometric colleagues about CVI. He recently taught a class of 250 eye doctors about CVI, using Sebastian’s case study as one example of how CVI can manifest.

I recently attended a virtual lecture with Dr. Arvind Chandna and Professor Gordon Dutton. There was a fabulous moment when Dr. Chandna spoke about the length of time it takes between when light first enters the eye and when conscious visual perception takes place. Dr. Chandna said that it takes about a tenth of a second after light passes through the eye, is converted to an electrical signal and travels through the optic nerve, past the lateral geniculate nuclei (LGN), and then to the back of the brain before there is any conscious perception of sight.

In other words, we literally see with our brains, not with our eyes.

I frequently see CVI described as a condition “where the eyes see normally, but the brain just can’t process what the eyes see.” This statement is just not accurate. Continuing to describe CVI this way is a tragic mistake with real, harmful results for people who have it.

In what way is that statement harmful? CVI is complex, and the statement above seems like a harmless way for a parent or low vision professional to give a two-second explanation of CVI.

All of us CVI parents need that two-second description of what CVI is to explain to the nosy mom on the playground or whatever, right? As CVI ambassadors, we need to do our best to make sure that the information that gets out to the world about CVI is factual.

The problem with claiming that CVI is a condition “where the eyes see normally, but the brain just can’t process what the eyes see” is that it it’s wrong. It leads typically sighted people to believe that CVIers are intellectually disabled, not blind/visually impaired.

Our eyes just collect light and pass signals to the brain.That’s it. Our eyes see nothing on their own.

The vast majority of the billions of people on this planet have never heard of CVI. That means that every CVI parent, caregiver, and low vision professional is a CVI ambassador, if you will, whether they want to be one or not. Decades of false claims about CVI, like the one we are discussing, have resulted in real harms to countless millions of CVIers.

Seeing is easy for typically sighted people. It’s automatic. I’ve been speaking, writing, and advocating for people who have CVI for five years. The vast majority of typically sighted people have never heard of CVI, and they can’t imagine not understanding what they see. Seeing is so easy for them, they can’t imagine the possibility of not understanding what they see.

I have found that when typically sighted people hear the phrase “CVI is a condition where the eyes see normally, but the brain just can’t interpret what the eyes see,” they immediately picture a normal, easy to understand visual scene – like on a movie screen – within a brain. They imagine that the brain itself is like a tiny cartoonish figure with very low intelligence, peering at the perfect image on the screen – with healthy, typical vision – and trying but failing to figure out what the image is.

When typically sighted individuals are taught that “CVI is a condition where the eyes see normally but the brain just can’t process what they see,” they inevitably assume that CVIers are intellectually disabled and not visually impaired. Worse, they believe that they can cure CVI by just explaining what things look like to people who have it. Neither of these assumptions is true.

CVIers don’t see what typically sighted people see. Period.

Everyone who has ever spent any time listening to people who have CVI understands how significantly different and disabling CVI vision is compared to typical vision. All people who have CVI are visually impaired. All of the adult and teen CVIers that I’ve had the honor of becoming friends with have been deeply harmed emotionally, psychologically, and educationally by typically sighted peoples’ demands that they “learn to see” by “trying harder,” “staring longer,” and “stop faking” their blindness.

We know that Sebastian’s tremendous efforts to teach himself to see by using art to memorize all the salient characteristics of absolutely everything and everyone he encountered didn’t “cure” his CVI, it concealed it from everyone. He chose to spend thousands of hours of his childhood drawing, painting, and sculpting in order to figure out and memorize all of the salient features of everything around him so that he could understand the world.

While his use of verbal mediation to process his vision is highly useful, I wonder what his childhood would have been like had he been diagnosed with CVI right away. While we are very proud of Sebastian’s artistic ability, the reality is that no child with CVI should have to teach themselves to draw with photographic realism in order to function in this world. They need to be taught blind skills early on so that they can enjoy living life fully, just like their typically sighted peers.

I am a huge fan of Kristen Smedley, the author of Thriving Blind and the creator of the Thriving Blind Academy. Although her sons both have ocular blindness, I believe that many of her practical suggestions for academic and career success apply to families with children who have CVI as well. We’ll never know what Sebastian might have chosen to focus on in childhood if we’d known about his CVI. Maybe he would have chosen to focus on art anyway. He’s extremely artistic, and the hours he spent creating art were always joyful, so I don’t regret the time he spent making art. I just can’t help but wonder.

So if it’s incorrect to say that CVI is a condition where the eyes see normally but the brain just can’t process what the eyes see, how would you recommend parents and low vision professionals explain CVI when they need a quick description?

That’s easy! When I need a one sentence description for CVI, I say,

“CVI is a brain-based vision impairment (or blindness) that is entirely different from ocular vision impairments.”

When people need a little more information, I follow up with “It’s common for people who have CVI to have normal acuity.” The beauty of these two statements about CVI is that they are actually true, and they don’t falsely imply intellectual disability.

What other issues in the CVI community concern you?

There are so many! I think my greatest concern is the overselling of neuroplasticity as a “cure” for CVI. We personally experienced a neuro optometrist who claimed that they could cure Sebastian’s CVI with “vision therapy.” This doctor told us that if Sebastian’s vision channels weren’t working, then Sebastian could just “use another channel” to see.

This doctor seemed to believe that neuroplasticity was something like operating a TV. You just press the “try harder to see” button, and bam! Another channel opens up like magic! Of course, when the vision therapy was completely ineffective, this doctor blamed Sebastian for not trying and being uncooperative. They said that Sebastian “could see if he would try harder.” Trying harder has never cured brain damage, yet I personally know many CVIers routinely face(d) the same accusations and recriminations as my son did.

That said, I am not against all vision therapy. There is actual scientific research demonstrating that vision therapy can be effective for treating some oculomotor conditions such as convergence insufficiency. My son’s convergence insufficiency was treated successfully by a different doctor, and it resulted in a measurable improvement in his ability to locate where an object was in space. When you have very little vision, every gain is a positive one.

However, just like cerebral palsy, CVI is a permanent condition. Despite that fact, I know that CVI families routinely encounter low vision professionals offering suspect cures for CVI just like we did. One family I know told me that they recently had an eye doctor claim he could cure their child’s CVI using trinkets, sacred geometry, tuning forks, and divination. These so-called therapies aren’t covered by insurance for a reason. There’s no evidence they work.

The worst thing about our own experience with CVI quackery is that I went into our experience with the first vision therapist knowing that there is no cure for brain damage.These quacks prey on terrified parents. I was so terrified for Sebastian’s safety, I was willing to do anything to try to help him. We didn’t have a diagnosis for Sebastian yet, and I was desperate to get him the orientation and mobility training that he needed to live independently. I desperately wanted this doctor to diagnose Sebastian and prescribe the O&M.

I could not afford to throw my money away on this, but I did anyway. Sebastian’s life was in danger. He could never safely live independently without O&M training with a white cane. I was desperate that any part of the therapy might help. It was like throwing spaghetti at the wall to see what might stick.

Instead of helping Sebastian, the “vision therapy” and subsequent attacks on his character was traumatizing. I know that many parents of children who have CVI are equally frightened for the child’s future and their safety. I have so much compassion for parents of children who are newly diagnosed with CVI. I know I would have moved mountains to help my son. I would have tried anything if I thought it would keep him safe.

I did try everything. That’s why I think we need stronger safeguards for these vulnerable, grieving families. Everyone needs hope, but false hope isn’t helpful for anyone. CVI parents are easy targets for these scam artists. I know I was.

We need solid, real research into what therapies actually help, instead of just personal anecdotes and Facebook posts. Children who have CVI can be trained to mimic typically sighted behaviors just as autistic children can be trained to mimic neurotypical behaviors with ABA therapy. CVIers also frequently teach themselves to identify things and people by their salient characteristics. Neither staring on command or correctly guessing who or what something is means the child’s CVI is becoming typical.

I can see how this would be important to you. What are your goals now?

I think that one of the biggest problems in the CVI community currently is the difficulty that many low vision professionals and parents have in understanding the difference between visual recognition and visual identification. It’s my goal to help end the confusion. This confusion is understandable, because the two abilities look identical to an outside observer. Sebastian’s ability to visually identify everything and everyone with virtually zero ability to visually recognize makes him appear to be completely typically sighted, despite being almost completely blind. It’s a miracle we discovered his CVI at all.

Understanding the difference between visual recognition and visual identification is important, because failing to discriminate between the two abilities often leads to dangerous misunderstandings about the severity of an individual’s CVIers; Conflating the two abilities also regularly results in false claims of a cure for CVI.

So what is the difference between visual recognition and visual identification?

Thank you for asking! Before I knew that Sebastian could see with words, I assumed that visual recognition and visual identification were exactly the same thing.

Before I explain, I think that it’s very important for typically sighted people to realize that people who have CVI can have a typical ability to visually recognize some things, but no ability to recognize others, depending on where their brain damage is located. Just because a person who has CVI can reliably recognize objects, for example, doesn’t automatically mean that they are going to be able to recognize symbols, or people. The only things that Sebastian is able to visually recognize like a typically sighted person can are words, letters, numbers, and symbols. He has no ability to recognize faces, places, objects, or biological forms.

Visual recognition is the ability to store a visual memory of an object, person, scene, symbol, letter, or word, etc. in the brain, and then to be able to match the new incoming image to the previously stored image. The brain then compares the two images, classifies the new image, and then identifies the new image. Visual recognition is a three-step process that ends with visual identification. Visual recognition is effortless and happens automatically for people with typical vision.

Visual identification (without neurotypical visual recognition) is completely different from visual recognition.

It is a handy skill to have for a person who has CVI, but it is not the same effortless process as visual recognition is to a typically sighted person. When a CVIer has ventral stream processing issues with recognition, whether it’s faces, places, objects, symbols, etc., the brain struggles to (or simply can’t) store an image to which it can later compare to new input.

When CVIers can’t recognize something or someone visually, they have to use visual clues to help them guess what something or someone is in order to (hopefully) correctly identify it. Many CVIers have simultanagnosia, and/or visual field losses that prevent them from even seeing an entire image, person, or face at one time. The ability to guess who or what something is from visual clues without having any mental image to compare to is visual identification. Those visual clues can be anything from color, shape, size, hair color, distinguishing features like facial hair, etc.

Guessing the correct answer is not the same thing as visually recognizing. It’s a guess. Even if it’s an accurate guess, it’s still a guess.

It’s common for CVIers to teach themselves how to memorize the salient characteristics of different objects and people, and then try to guess who or what different people or objects are based on their characteristics. They also routinely use every tool at their disposal to help them guess correctly, including logic, location, texture, and scent. This is what Sebastian does. He happens to be an extraordinarily good guesser with a fabulous memory for detail. He passes for typically sighted because he is so good at guessing.

With thousands of hours of practice drawing, painting, and sculpting everything around him, Sebastian’s brain even developed the neuroplastic ability to give him a brief glimpse of the object or person in question. When he thinks the word descriptors of whatever he is looking at, Sebastian gets a momentary, fleeting, glimpse that leaves no impression in his visual memory at all. It’s a flash of understanding. Sebastian says that he “gets an idea of it” when he uses his verbal mediation to guess what an object or person is.

However, Sebastian’s neuroplastic verbal mediation did not cure his vision, and it did not make his vision typical. His use of verbal mediation to process his vision successfully and completely concealed his severe CVI. Sebastian’s CVI is so bad that he actually has no conscious perception of sight at all when he’s not actively thinking descriptor words. He goes entirely blind.

When typically sighted people don’t understand the difference between visual recognition and visual identification, CVIers suffer. All the CVIers that I know commonly experience verbal and emotional abuse from typically sighted people because they can recognize some things, but not others, or because they often can successfully guess what some things are using visual clues to identify things, but not consistently. They often are accused of faking their visual impairment because the people around them think that if a CVIer can recognize one thing, then they can recognize everything.

We experienced horrific abuse from low vision professionals because Sebastian can read. To them, that meant his vision was typical. They seemed to believe that human vision evolved for the single purpose of reading and nothing else. When parents and low vision professionals assume a child’s vision is being cured because the child has just learned to become a better guesser, or because they can visually recognize some things – but not everything – those assumptions often result in a total failure to understand the severity of the child’s vision impairment.

You raise some interesting points about the importance of understanding the difference between visual recognition and visual identification. I can understand why people assume they are the same. When a child is shown a picture of an elephant and guesses that it’s an elephant, there’s no way to tell how the child is arriving at the correct answer. It’s truly an invisible process. Why else is it important to understand the difference between visual recognition and visual identification?

I think that we are at a crucial juncture in time. Now that we have a better understanding of how ventral stream processing works and what visual memory actually is, we can finally begin to apply what we know to understanding how to help children learn. If my son can only visually recognize words, letters, numbers, and symbols the way that typically sighted people do, that’s because the parts of his brain that are used in the visual recognition of words, letters, numbers and symbols are intact.

I personally know several CVIers and/or the parents of CVIers who have struggled exhaustively with learning numeracy and literacy who are now, after a very belated CVI diagnosis, having tremendous success with braille. After years of tears and frustration, suddenly tactile learning has made enormous educational progress possible. These are families who have done and tried every reading and math learning technique imaginable

While braille isn’t accessible to all CVIers, especially those with cerebral palsy, it certainly should be considered for those with the physical ability to try it. Education is a human right, and CVIers have a right to the most accessible methods of learning, including tactile instruction when needed.

It must have been vindicating when you finally had the fMRI images of Sebastian’s ability to see with words from the Harvard CVI Neuroplasticity research study. I’m glad you brought up neuroplasticity before. Tell us more about that experience.

When Dr. Merabet sent me the fMRI images back in the spring of 2018, it was vindicating, and life-saving. Sebastian and I had been labeled crazy by the medical establishment for seeking a diagnosis for Sebastian’s CVI. We are so incredibly grateful to Dr. Barry Kran for diagnosing Sebastian’s CVI, and to Dr. Lotfi Merabet for confirming what we discovered at home; Sebastian sees with words. They literally saved Sebastian and me from a lifetime of medical malpractice and abuse.

Neuroplasticity is real. All of us have it. It’s a fancy word for what the brain does when it’s learning. It creates new connections, and those connections are really huge in number when the brain is still growing in size between birth and age three. However, neuroplasticity is not a cure for brain damage. The areas of the brain that are dead do not regrow – they remain dead.

One of the reasons we struggled to get a diagnosis for Sebastian was because, like many CVIers, Sebastian has a normal-appearing MRI. There are no visible lesions on his CT scans or his MRI scans. We had to travel to Paris to get a SPECT scan to find Sebastian’s brain damage.

A SPECT scan is a nuclear medicine test that measures blood flow to the brain. Any areas of the brain that are not receiving blood are dead tissue.

We found significant brain damage once we were able to look at how Sebastian’s brain was actually functioning instead of just looking at its structure. Sebastian’s many thousands of hours developing his neuroplastic verbal mediation to process his vision through drawing and painting didn’t cure his brain damage, or his CVI. Sebastian’s brain damage is all still there. That’s why he’s blind.

I absolutely believe in miracles. I have experienced miraculous events, and it’s certainly possible that someone, somewhere, has experienced a cure for their brain damage. However, I think it’s crucial for parents, medical professionals, and TVIs to temper their expectations and be realistic. The fact is, all across the world, people who have ocular forms of visual impairment routinely use salient characteristics to guess who or what they encounter, and no one anywhere uses their excellent guess work as proof of a cure for their ocular vision problems. People who have CVI need the same understanding and realistic expectations.

CVIers frequently find that using their vision, whether they are using salient characteristics or not, is visually exhausting, unrelenting labor. When parents, educators, and medical professionals assume that a child’s vision is becoming typical simply because the child is becoming better at guessing who and what things and people are, these false assumptions can set the child up for a lifetime of unrealistic expectations. Then, when the child continues to struggle visually, they face false accusations of faking their blindness, having mental health issues, and/or having behavior disorders because they still have CVI.

It is devastating to the human spirit to be called a liar, a fake, intellectually disabled, or mentally ill just for using the exact same compensatory strategies that people with ocular vision impairments use every day. Neuroplasticity is a real phenomenon of human existence, and children who have CVI can make some gains in their vision. I personally believe that seeing with words is a teachable skill if it’s started young enough and, more importantly, if the child shows interest. It’s important that everyone has realistic expectations of how much CVI can truly improve, and to provide opportunities for multisensory learning experiences to children who have CVI as appropriate.

Technology has advanced so far that no educator or future employers should be the least bit concerned about whether an individual prefers one mode over another to perform communication tasks. Using braille needs to be normalized for the CVIers who prefer it.

Do you have anything else you like to share with our readers about CVI?

I personally believe that every human, speaking or non-speaking, is a thinking, feeling person with something important to contribute to society. Recently, David Teplitz and Hari Srinivasen make history as the first non-speaking autistic graduates at U.C. California. As a teacher, I have had the joy of working with many non-speaking individuals. I am haunted by the non-speaking students that I had thirty years ago that I am now certain had CVI and CAPD, and who I believe were misdiagnosed with autism.

It is my opinion that one of the greatest tragedies of our time is the failure to recognize deafblindness as a spectrum disorder. Every day, it seems like we are learning more and more about the connection between CVI and central auditory processing disorder (CAPD), and their combined effects on ambient learning of language and absolutely everything else. Sebastian has CAPD, as do large numbers of other CVIers. I think as more research is conducted, the link between our visual and auditory processing will become more apparent.

Just as CVIers can perceive light but they can’t (or they struggle to) translate the light into meaningful images, people who have auditory processing disorders can hear sound. They can’t (or they struggle to) translate those sounds into meaningful language. My blind son passed every vision test, every year, because he has normal acuity. Likewise, I believe that thousands of children with CAPD pass their hearing screenings because they can perceive sound. They struggle to understand what they hear, which sets them up for a lifetime of social, educational, and personal struggles.

There is a window for language acquisition in early childhood. We know that neurotypical children raised in abusive/feral situations where they are deprived of human contact and language lose the ability to acquire speech later. This loss of the ability to acquire language is permanent, even when the children are later put into loving, therapeutic homes. Right now, the average age when children begin to be tested for CAPD is seven. That means that many children who have CAPD have lived for seven years without access to meaningful human language and communication before they have even begun to be tested.

Human infants don’t know any language, so there is no possible way (at this time) to test babies’ abilities to understand a language that they don’t yet know. We need more research on CVI and CAPD, and we desperately need parents of at-risk children to know that early intervention with ASL or ProTactile sign language may be hugely beneficial to their children. I did baby signs with Sebastian beginning when he was about two weeks old, and I’m so glad that I did.

All of the research shows that hearing children who also learn sign language at home have better language development than hearing children who only experience spoken language. There is literally no downside to doing sign language with a baby who has (or is suspected of having) CVI and possibly CAPD. I know that if I had known that Sebastian had CVI and CAPD, I would have eagerly embraced learning proTactile sign language with him as an infant.

After your book came out, was there anything that surprised you?

The reason I wrote Eyeless Mind was because I knew that there must be others out there like Sebastian. I was certain to the depths of my soul that there were other CVIers suffering from long-time denial of their blindness. Once we went public, I was surprised at how quickly people came forward. The friendships that I have formed with CVIers and their wonderful families are precious to me.

We are the walking wounded. Like Sebastian’s story, my CVIer friends’ stories of medical and educational malpractice are beyond the pale and entirely unacceptable in a so-called “civilized” society. In many ways, we are triply traumatized. First, we (or our children who have CVI) are traumatized from the terror of years of being blind and having nobody know. Then, we are (or were) abused by a broken and completely dysfunctional educational system. Finally, we are “welcomed” into a CVI community that not only doesn’t want to recognize our children as CVIers, but that has actively spent years using misinformation and science denial to falsely label our children as learning disabled instead of blind/visually impaired.

All people who have CVI are deserving of the human right of early identification, accurate diagnosis, and access to appropriate educational and habilitative supports. All of them, my son included. CVI and CAPD have been around as long as humans have. It is the responsibility of typically sighted low vision professionals and parents to be life-long learners. There is no better way to understand the functional vision of people who have CVI than to talk to people who have it. I am so thrilled to see that Perkins is featuring speakers who have CVI at the upcoming Collaboration for Change conference, including my dear friend Nai Damato.

I have enormous compassion and sympathy for all CVIers, and for their families. I would never want any child who has CVI to go without appropriate educational and/or life-saving O&M services as my son did. It has been three and a half years since we first went public with our story. I am asking – again – for the same compassion from everyone in the CVI community.

I want to be clear that I’m not asking for anything for myself or my son. We know that we are incredibly blessed. I’m incredibly lucky that, despite all the trauma, my son is slowly recovering. Who knows? Maybe someday, I might even begin to recover. I look forward to the day when I can literally release the weight of this burden of advocacy.

I didn’t understand the concept of emotional labor until I became a CVI advocate. It never gets easier to talk about what happened to us. I am asking for the CVI community to come together for the countless other families out there whose children, like Sebastian, don’t fit in a stereotypical, outdated concept of what CVI is “supposed to” look like. Their lives are important, too.

To Read Stephanie’s book: Eyeless Mind click this link.