Anne Spitz, Teacher of the Visually Impaired, Dover, MA

Anna Swenson, Braille Literacy Consultant, Fairfax, VA

Acknowledgements: Many of the ideas in this article were suggested by Connecticut teachers of the visually impaired attending a state-wide workshop on Braille Literacy Techniques, April 30-May 1, 2013. Other contributors include Tracey O’Malley and Valerie Blane, teachers of the visually impaired in the Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia, and the conference co-presenters, Anna Swenson and Anne Spitz.

Older elementary or secondary school students with visual impairments who already know how to read in print may begin learning braille for a variety of reasons. Some may have experienced a sudden visual loss or have a visual condition that is unstable or progressively deteriorating. In many cases, braille is considered when a functional vision / learning media assessment documents that a student’s use of print is slow, fatiguing, or inefficient, making it difficult to keep up with academic work. In deciding to add braille to the IEP, the team may also be concerned about future literacy skills as print becomes smaller and reading demands heavier.

Many people do not realize that braille is legally the default literacy medium for any student who is blind or visually impaired. According to IDEA (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act): The IEP team must—* * * (iii) in the case of a child who is blind or visually impaired, provide for instruction in Braille and the use of Braille unless the IEP team determines, after an evaluation of the child’s reading and writing skills, needs, and appropriate reading and writing media (including an evaluation of the child’s future needs for instruction in Braille or the use of Braille), that instruction in Braille or the use of Braille is not appropriate for the child …” (Educating Blind and Visually Impaired Students; Policy Guidance; Federal Register; Vol. 65, No. 111; Thursday, June 8, 2000 http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2000-06-08/pdf/00-14485.pdf) This section of the law highlights the importance of regular functional vision /learning media assessments and the need for braille instruction to be reviewed at every IEP meeting.

Very little research or practical information is available to guide teachers as they introduce braille to former or current print readers. Finding appropriate instructional materials, motivating students to persevere with learning braille, and carving out sufficient time for instruction all pose potential challenges.

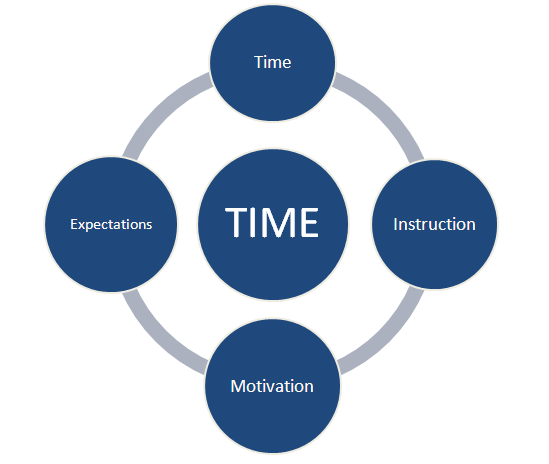

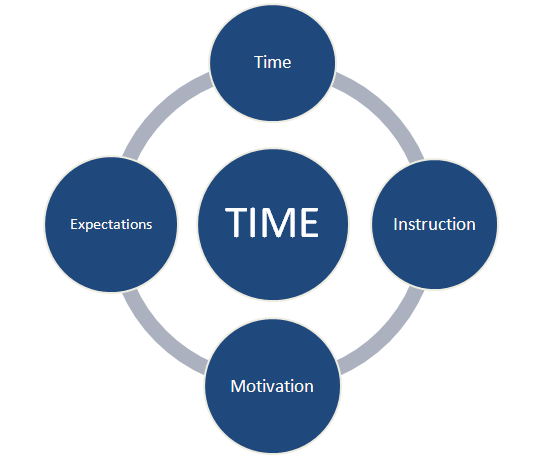

For this workshop, the acronym “TIME” was used to organize a discussion about the challenges and expectations involved in teaching braille to students with established print literacy skills.

- T = Time: How much service time should I provide? How do I find time to teach braille? How do I integrate braille into the curriculum?

- I = Instruction: What approach(es) can I use to teach braille? (commercial & teacher-designed). How do I balance fluency with learning the code? Which is more important, fluent reading or knowing the entire code?

- M = Motivation: How can I motivate my student to learn braille?

- E = Expectations: What are the goals of braille instruction? How will braille benefit my student in school? After high school graduation?

Listed below are suggested activities, resources, and teaching strategies for each of these areas. We hope they will be useful to other TVIs as they work with print readers who are transitioning to braille or learning braille as an additional literacy medium. Note that some of the suggestions apply to more than one area.

Time

- Schedule lessons a minimum of twice a week (with homework); a service time of once a week (or less) is ineffective.

- Aim for consistency in the number of lessons per week and the length of the lessons at the beginning. Later, as the student makes progress and begins to integrate braille into his/her classwork, more flexibility in service delivery may be appropriate.

- Analyze the student’s schedule for potential segments of instructional time, even if they are short: “early bird” work time at the beginning of the day (elementary); study breaks; before / after school.

- Plan a Skype visit between lessons to check on the student.

- Offer braille as a high school elective during a “study skills” or “basic skills” class. Negotiate credit for the class.

- Start a Braille Club open to typically sighted peers and student(s) with visual impairments. The student who is visually impaired can learn along with his/her peers or co-instruct.

- Integrate braille into one or two subjects or courses, e.g., spelling.

- Use a trained paraprofessional for reinforcement.

- Take advantage of ESY (Extended School Year) services to maintain skills over the summer.

Instruction

- General guidelines: build in success; aim for automatic recognition of letters, contractions, and words (over-learning); document progress regularly and share the data with the student.

- Balance learning the code with fluency. Both code knowledge and fluency are important.

- Make the focus of instruction relevant and integrated into students’ lives:

- Conduct an interest inventory

- Use articles from teen magazines, information from web sites, song lyrics, poems, or passages from favorite books for reading practice

- Have the student use braille for functional purposes: shopping lists; directions to a mobility lesson destination; labeling; file of friends’ birthdays or phone numbers

- Consider commercial resources for teaching braille. Note that a combination of resources is often more effective than a single program.

- The Mangold Developmental Program of Tactile Perception and Braille Letter Recognition (Exceptional Teaching): Designed to teach efficient tracking and the letters of the alphabet.

- Braille FUNdamentals (TSBVI): Sequenced instruction in the braille code at four different reading levels with suggestions for games and other activities. A special feature in Duxbury enables the teacher to transcribe materials using only the contractions a student has learned in the Braille FUNdamentals curriculum.

- Sections of Building on Patterns (APH): Building on Patterns is a complete reading program designed for children in grades K-3. The content is often not appropriate for older students and, if the student is already a print reader, only portions of the curriculum will be relevant.

- The Braille Connection (APH): Designed for adults and teens who are former print users. Note: Several teachers commented that this program lacked relevance for their teen-aged students.

- I-M-ABLE (Individualized Meaning-centered Approach to Braille Literacy Education, Diane Wormsley): A highly individualized method that starts with key words of interest to the student and uses them to build letter/contraction recognition, efficient tracking, and fluent reading. Resource: Braille Literacy: A Functional Approach by Diane P. Wormsley, AFB Press. One secondary resource room teacher uses this approach exclusively with her dual media learners.

- Read Naturally www.readnaturally.com: A structured program to build fluency; designed for print readers, but easily adapted for braille learners; used by many teachers of students with learning disabilities

- Guided reading materials or high interest / low vocabulary books from general and special education. Introducing contractions as they appear in the student’s reading is another option for instruction.

- Activities: Have the student …

- Participate in a written dialogue with the teacher

- Read a familiar book in print, then in braille

- Read his/her own writing in braille, e.g., an assignment written on the computer transcribed by the teacher

- Substitute a braille assignment for a visual assignment, e.g., compose a poem in braille in place of completing a word search

- Expose the student to technology, such as notetakers and braille displays for computers and i-Pads.

Motivation

- Work to develop a personal connection with the student and his/her family. Understand that it may take time for them to accept the need for braille and appreciate its value.

- Share resources related to braille with the student and family. Take every opportunity to demonstrate the value of braille.

- Work with the student and his/her family to set goals for reading, writing, and using braille. Record and reward progress.

- Make braille functional – teach what the student needs to know first. Find real-life uses for braille whenever possible (see Instruction and Expectation sections).

- Individualize each lesson by including content of particular interest to the student.

- Integrate technology (especially devices with refreshable braille displays) into the lessons.

- Challenge the student to compete against him/herself when working on character/word recognition, reading fluency, or other skills. Have the student keep a visual or tactile record (e.g., chart, graph, notetaker file) of progress.

- Videotape the student reading to document hand movements and fluency. Analyze the video with the student to discuss progress and next steps.

- Have the student keep track of the number of pages read and/or participate in the annual Braille Readers Are Leaders contest (National Federation of the Blind).

- Have the student keep an experience journal about learning braille – or any other topic of interest.

- Plan a scavenger hunt; play games commercially available in braille (Uno, Scrabble, BrainQuest); research or create other games (Braille FUNdamentals has many suggestions for games appropriate for all ages).

- Consider having students watch movies related to blindness – after previewing them and consulting with the family. Suggested movies include: Blindsight; The Renegades: A Beep Ball Story; and The Eyes of Me.

- Arrange for the student to teach braille to his/her peers. For elementary school children, indoor recess is often a good time. Consider a Braille Club for upper elementary and older students.

- Introduce the student and his/her classmates to the Braille Bug website http://www.braillebug.org/ (elementary).

- Arrange for the student to give a mini-presentation about braille to his/her teachers during a collaborative planning meeting.

- Arrange for a secondary student to give a braille presentation to an elementary class. Collaborate with the mobility instructor if transportation is needed; this would also be a good opportunity for the student to work on O&M skills in an unfamiliar environment.

- Have older students read braille to younger children.

- Locate a braille pen pal with similar interests.

- Find a mentor who uses braille – an older student, a college student, or an adult.

- Use “bribes”: Special mobility lessons, concert tickets, lunch bunch with friends (elementary). One teacher reported that her student learned braille when his parents agreed to pay him for his progress!

- Negotiate compromise: In certain situations, a student may reach a level where service time for braille instruction can be decreased, suspended temporarily, or stopped altogether. Although this is an IEP team decision, the student should play a major role in crafting the compromise.

Expectations

(Note: Expectations will vary for individual students)

Students will …

- Understand that braille is one tool in their “toolbox”. Learn to choose appropriate literacy tools for different situations. Aim for independence and efficiency.

- Use braille for academic work in meaningful and purposeful ways. For example, have the student read (and/or write) some of the following in braille:

- Spelling words

- Vocabulary words (e.g., at a beginning level, match words in braille to definitions in print)

- The daily schedule or agenda

- Written teacher feedback about an assignment

- Notes for an oral presentation

- Use braille in conjunction with technology:

- Notetaker

- Bookshare and other e-books

- Refreshable braille display for laptop and/or i-Pad; learn to proofread writing using a refreshable braille display.

- Use braille labels to organize school binders and other materials. Label print papers to identify them, e.g., write “h” on a history assignment as it comes out of the printer.

- Use braille for labeling items at home (medications, spice jars, etc.), reading recipes, and facilitating other daily living tasks.

- Prepare braille notes for participation in an IEP meeting (strengths, needs, etc.) or a job interview.

- Read shorter (e.g., poetry) or longer (e.g., novel) braille texts fluently and independently.

- Read braille books to younger children in the family.

Additional Resources

Braille and Visually Impaired Students: What does the law require? (NFB). A brochure outlining the legal requirements for braille instruction in a simple question-answer format. Available at: https://nfb.org/braille-and-vi-students

Integrating Print and Braille: A Recipe for Literacy (NFB): A short book focusing on braille instruction for dual media learners. It includes teaching strategies, case studies, and suggestions for integrating both print and braille into students’ lives. The complete book can be found on the Paths to Literacy website at: http://www.pathstoliteracy.org/resources/integrating-print-and-braille-recipe-literacy

Literacy Instruction for Students who are Blind: A Framework for Delivery of Instruction by Alan Koenig and Cay Holbrook. A detailed resource designed to assist IEP teams in determining the appropriate amount, consistency, and duration of service time for braille literacy instruction at all levels. Found on the Paths to Literacy website at: https://www.pathstoliteracy.org/resource/project-slate-framework-braille-literacy-instruction/

Braille Institute, Los Angeles: The Braille Special Collection / Partners in Literacy Program – Any visually impaired child between the ages of 3 and 18 living in the United States or Canada OR any teacher of the visually impaired is eligible to receive up to twelve free books per year through the Braille Special Collection Program. The collection offers a variety of books for students of different ages. “Dots for Tots” board books for preschool children include delightful manipulatives to reinforce story content. “TacTales” books feature tactile illustrations, and “Top Dot” products are specifically designed to help children ages 4-7 develop vocabulary and other language skills. Books for older students are often transcriptions of recently published print books, not available elsewhere in braille. Books may be requested by families for a child who reads braille or by teachers through the Partners in Literacy program.

- For more information, visit www.brailleinstitute.org. Click on “Services”, “Braille Publishing”, and “Braille Books for Children”.

- To sign up for the Braille Special Collection (families) or the Partners in Literacy program (teachers):

- Call 1-800-BRAILLE and ask for Braille Publishing, or call directly to 323-906-3104. Ask for Jackie Garcia. M-F 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM (PST)

- E-mail jgarcia@brailleinstitute.org (Calling is recommended.)