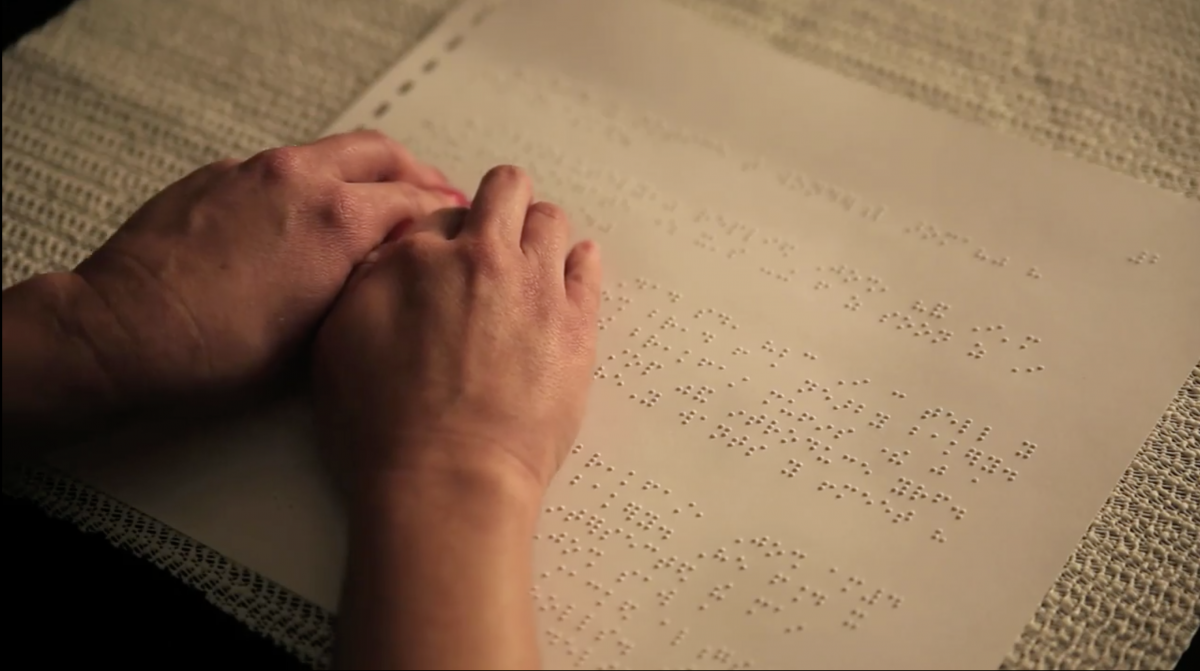

The CCSS, Foundational Skills define the beginning processes for learning to read. Students who are sighted learn to read print visually, e.g., learning the letters of the alphabet and concepts of words incidentally (seeing objects and actions in their daily environment and imitating the behaviors of others). Whereas, students who use braille typically are not exposed to braille until they began receiving direct instruction from a teacher of the visually impaired (TVI). Students who are sighted see print daily for example, on television, street signs, menus, and items in the grocery store. However, students who use braille do not have daily exposure to braille and when braille is present they must be told it is there before they can explore it. As a result students who use braille do not have the same access to braille and require direct instruction to learn basic reading foundational skills. Additionally, students who use braille must develop crucial skills that are unique to braille readers, i.e., they must develop tactile sensitivity and proper hand movement techniques to read braille fluently. Therefore, this page dedicated braille hand movement patterns and refreshable braille displays is included on this website.

Braille Hand Movement Patterns

Hand movement patterns are an important aspect of reading speed and accuracy because braille readers must be able to use their hands and fingers to quickly and accurately identify letters and characters in a brailled text to become efficient readers. The most efficient hand movement patterns are two-hand movement patterns (i.e. the split or scissors patterns).

Braille readers must be taught efficient ways to read tactilely to become fluent readers. It is important that TVIs instill in their students who are learning braille the correct use of the fingers and hands when braille reading instruction begins. Kusajima (1974) established a model of hand movement patterns which is still currently used among braille readers. Kusajima divided braille hand movement patterns into two categories: one-handed and two-handed braille reading. Braille readers who read with one-hand will either read with their right or left hand. In two-handed reading there are four hand movement patterns which are: 1) left hand marks; 2) parallel; 3) split; and 4) scissors.

In this video, Tessa McCarthy examines strategies for helping beginning braille readers have optimum hand movements to help them be fluid braille readers.

Left Hand Marks Hand Movement Pattern

With the left hand marks pattern the left hand waits at the beginning of the braille line while the right hand reads the braille line. At some point before the right hand finishes reading the braille line the left hand drops down to the next braille line and waits for the right hand. When the right hand reaches the end of the braille line it quickly moves down to the next braille line meeting the left hand and begins reading the braille line and this process continues to repeat.

Parallel Hand Movement Pattern

When using the parallel pattern both hands remain together as they read the braille line. When both hands reach the end of a braille line the hands remain together as they drop down to the next braille line and the hands repeat this pattern as they continue to read.

Split Hand Movement Pattern

In a split pattern both hands read together until nearing the end of the braille line at which point the left hand drops down to the next braille line and waits until the right hand finishes reading the braille line. When the right hand reaches the end of the braille line it quickly joins the left hand and the two hands begin reading the next braille line repeating the same pattern.

Scissors Hand Movement Pattern

With the scissors pattern the two hands read independently of each other. The left hand begins reading the braille line and when it reaches the middle of the braille line the right hand touches it and continues reading until it reaches the end of the braille line. While the right hand finishes reading the braille line the left hand drops down to the beginning of the next braille line and begins reading the new line of braille. When the right hand finishes the previous braille line it touches the left hand as it reaches the middle of the braille line and takes over reading to the end of the braille line as both hands continue to repeat this reading process (Kusajima, 1974; Wormsley, 1979; Wright, Wormsley, & Kamei-Hannan, 2009).

Characteristics of Hand Movements

As braille readers learn to read using the correct hand movement patterns it is important for TVIs to pay close attention to the braille readers use of characteristics of hand movements during braille reading instruction. Characteristics of hand movements are the unique reading characteristics that relate to braille reading. Students who use braille may read using one or more of the six characteristics of hand movements which are: 1) scrubbing, 2) pausing, 3) erratic, 4) regression, 5) searching, and 6) normal reading.

Scrubbing

When the braille reader is scrubbing they will move their finger up and down over a braille character, instead of moving their finger in a smooth motion reading the braille character from left to right. If the TVI notices the student exhibiting this characteristic it means the student is having trouble identifying the braille character and the TVI may need to provide further practice of the braille character with the student (Wormsley, 1979; Wright et al., 2009).

Pausing

When the braille reader pauses during braille reading the hand simply stops moving across the braille page (Wormsley, 1979; Wright et al., 2009).

Erratic

Erratic hand movement refers to any hand movement that is not related to reading, such as taking the hands off the braille page to flex the fingers, scratch, or to perform any task that is not related to reading (Wormsley, 1979; Wright et al., 2009).

Regressions

Regressions in braille reading is similar to that of print reading. When the braille reader regresses the hand or finger will jump back to re-read braille characters that have already been read on the same braille line. Often readers use regressions when they do not understand something they have read or if they want to re-read for clarity (Wormsley, 1979; Wright et al., 2009).

Searching

In a searching motion the braille reader will re-read something on a different line previously read or on a different page previously read. During a searching motion the reader may also skip ahead on the same page or flip to the next page of braille that has not been read (Wormsley, 1979; Wright et al., 2009).

Normal

In normal braille reading the braille reader moves the hands smoothly across the braille text line by line and does not demonstrate any of the characteristics of hand movements mentioned here (Wormsley, 1979; Wright et al., 2009).

Beginning braille skills are best taught to young beginning braille readers using embossed braille pages (Bickford & Falco, 2012; D’Andrea, 2012; Presley & D’Andrea, 2009). Students who use embossed braille learn essential reading skills such as the proper hand movement and finger positions. In addition, students who use embossed braille learn crucial reading skills such as, sentence structure, paragraph structure, grammar, and punctuation (D’Andrea, 2012). Although, it is important for young students who use braille to learn beginning reading skills using embossed braille, they should be introduced to electronic braille at an early age to familiarize them with a tool that will prove to be extremely beneficial as they progress in grade level (Coudert, trans. 2015).

Refreshable Braille Displays

As students who use braille develop a solid foundation in understanding the concepts of pages and paragraph through reading full pages of embossed brailled text they will increase their choices of braille reading tools available to them (Coudert, trans. 2015; D’Andrea, 2012). The high expectations of students as they progress in grade level will result in the need for students who use braille to develop proficient skills in the use of multiple devices to access their curriculum and complete school assignments in a timely manner. They will need to develop proficient skills in the use of assistive technology devices such as, refreshable braille displays to meet the rigorous demands of the CCSS. Refreshable (electronic) braille display refers to a single row of braille cells typically ranging from 18-80 braille cells. Each braille cell consists of six to eight plastic pins which are raised and lowered representing the braille dot configurations of a braille cell, and connect to computers or tablets using a USB cable or bluetooth. Furthermore, refreshable braille displays include navigations keys e.g., forward, back, up, and down (Presley & D’Andrea, 2012).

When reading on a refreshable braille display students can only see one line of text at a time therefore, the skills that are required for using a refreshable braille display are different from the skills that are required for reading embossed braille pages. Moreover, students will typically read with one hand on a refreshable braille display instead of reading with two hands, as they would when reading embossed braille pages. As a result, when reading on a refreshable braille display the hand movement methods that are use are different than the hand movement methods used to read embossed braille pages. This is because students will need to use their thumbs to operate the navigation keys to scroll through the text (Coudert, trans. 2015). Additionally students who use braille must learn numerous commands to efficiently complete tasks using the refreshable braille display (Hong, 2012).

According to researchers using a refreshable braille display is encouraging and produces positive outcomes for students who use braille (Bickford & Falco, 2012; Coudert; D’Andrea, 2012; Kamei-Hannan & Lawson, 2012). Some advantages to using a refreshable braille display include, ease of transporting, less space is required when reading, immediate access to printed material, and braille dots are crisp and easier to read (Bickford & Falco, 2012; D’Andrea, 2012). Although there are many advantages to using electronic braille students who use braille and TVIs agree that learning to read using embossed braille is an essential skill for beginning braille readers (Bickford & Falco, 2012; Coudert, trans. 2015; D’Andrea, 2012), partly due the fact that some formatting in paper braille can be lost on a refreshable braille display (Coudert, trans. 2015). Students who use braille must be skilled in the use multiple assistive technology devices to complete academic tasks. According to D’Andrea (2012) students use between four and eight devices to efficiently complete curriculum tasks. Therefore, students must develop proficient skills in the use of a wide variety of assistive technology tools and must be provided with several device choices to access curriculum and meet the same expectations as their sighted peers.

Resources

Foundations of Braille Literacy. (1994). New York: AFB Press.

Instructional Strategies for Braille Literacy. New York, NY: AFB Press.

National Braille Press: http://www.nbp.org/ic/nbp/programs/index

Bickford, J. O., & Falco, R. A. (2012). Technology for Early Braille Literacy: Comparison of Traditional Braille Instruction and Instruction with an Electronic Notetaker. Journal Of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 106(10), 679-693.

Coudert, C. (2015). Digital braille versus paper braille. Braille Monitor, 58(2).

D’Andrea, F. M. (2012). Preferences and practices among students who use braille and use assistive technology. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 106(10), 585-596.

Hong, S. (2012). An Alternative Option to Dedicated Braille Notetakers for People with Visual Impairments: Universal Technology for Better Access. Journal Of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 106(10), 650-655.

Kamei-Hannan, C., & Lawson, H. (2012). Impact of a Braille-Note on Writing: Evaluating the Process, Quality, and Attitudes of Three Students Who Are Visually Impaired. Journal Of Special Education Technology, 27(3), 1-14.

Kusajima, T. (1974). Visual reading and braille reading: An experimental investigation of the physiology and psychology of visual and tactual reading. New York: American Foundation for the Blind.

Presley, I & D’Andrea, F. M. (2009). Assistive technology for students who are blind or visually impaired: A guide to assessment. New York, NY: AFB Press

Wormsley, D.P. (1979). The effects of a hand movement training program on the hand movements and reading rates of young braille readers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA.

Wright, T., Wormsley, D. P., & Kamei-Hannan, C. (2009). Hand Movements and Braille Reading Efficiency: Data from the Alphabetic Braille and Contracted Braille Study. Journal Of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 103(10), 649-661.

This project was funded by the US Department of Education, Rehabilitation Services Administration (RSA), 84.235E Special Projects and Demonstrations for Providing Vocational Rehabilitation Services to Individuals with Severe Disabilities. The project is titled: Braille Brain: A Braille Training Program for pre/in-service Teachers of Students with Visual Impairments (TSVI), paraprofessionals, and other educational team members (H235E190002).

Braille Brain

Reading

- READING: Foundational Skills for Reading

- Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

- Vocabulary Acquisition and Use

- Braille Hand Movement and Refreshable Braille Displays

- Conventions of Standard English: Standard One

- Conventions of Standard English: Standard Two

- Writing and Language

- Craft and Structure

- Key Ideas and Details

- Best Practices for Teaching Braille and STEM to the Visually Impaired

- Assistive Technology to Support STEM Subjects for the Visually Impaired

- Compensatory Skills: A Focus on Organization

- Foundational Skills for STEM

- Math Instruction for Students with Visual Impairments

- Science Instruction for Students with Visual Impairments

- Tactile Graphics

STEM

- Best Practices for Teaching Braille and STEM to the Visually Impaired

- Assistive Technology to Support STEM Subjects for the Visually Impaired

- Compensatory Skills: A Focus on Organization

- Foundational Skills for STEM

- Math Instruction for Students with Visual Impairments

- Science Instruction for Students with Visual Impairments

- Tactile Graphics

- Braille Brain

- About Braille Brain

- Braille Training Program

- Foundational Skills for Reading

- Integration of Knowledge and Ideas

- Vocabulary Acquisition and Use

- Braille Hand Movement and Refreshable Braille Displays

- Conventions of Standard English: Standard One

- Conventions of Standard English: Standard Two

- Writing and Language

- Craft and Structure

- Key Ideas and Details

- Best Practices for Teaching Braille and STEM to the Visually Impaired

- Assistive Technology to Support STEM Subjects for the Visually Impaired

- Compensatory Skills: A Focus on Organization

- Foundational Skills for STEM

- Math Instruction for Students with Visual Impairments

- Science Instruction for Students with Visual Impairments

- Tactile Graphics